When the mammal collection of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin moves into new quarters, it will be catalogued and digitised in the process. A large part of the collection consists of horns and skulls of African antelopes. These are at the heart of a current research project in which the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin would like its visitors to participate. The idea is to foster interest in nature and to pass on insight from research directly to the public.

In the newly restored exhibition gallery, scientists can be watched going about their daily business, generating 3D surface models of antelope skulls. Scanning sessions take place from 10 October to 6 November 2017, Tuesdays to Saturdays 13:00 to 16:00.

The scientific collections of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin comprise over 30 million items covering biology, palaeontology, and mineralogy. They are complemented by our large library and the collections of the Animal Sound Archive, and the Department of Historical Research. One of the central tasks of the museum is to build digital collections and hence to broaden access through national and international research platforms.

Scientific information

Currently, parts of the mammal collection are moving from their former storage rooms to a new space accessible for visitors. In this process, the collection will be newly inventoried and digitized. A large part of this collection includes deer’s antlers or horns and skulls of African antelopes, the latter of which are the focus of an ongoing research project. In October and November, a number of antelope skulls – and the researchers studying them – will stopover briefly in a newly restored exhibition hall, providing visitors a chance to see research in action.

In Africa today, savanna habitats such as grasslands and woodlands support many different herbivorous mammals, including antelopes, giraffe, zebra, pigs, elephant, rhinos, and hippopotamus. This is even truer in the past, as it is common to find almost double the number of species at African fossil sites of the last 5 million years. Today, savanna herbivore species differ in body size and feeding strategies, reflecting their 'sharing' of the available vegetation. But how so many more species coexisted in the past is still unknown. Strong ecological differences are reflected in the shape of the skull, and our researchers are using this to investigate how competition for the same food resources in the past might have stimulated the evolution of the ecological diversity we see today.

Among African herbivores, antelopes are ideal for investigating coexistence and competition, because this group is very diverse and has a good fossil record. At one point in time, around 5 million years ago, most antelopes differed little in skull shape, indicating they had similar diets and habitats. Since then, African antelopes have evolved a bewildering diversity of skull forms reflecting distinct dietary preferences.

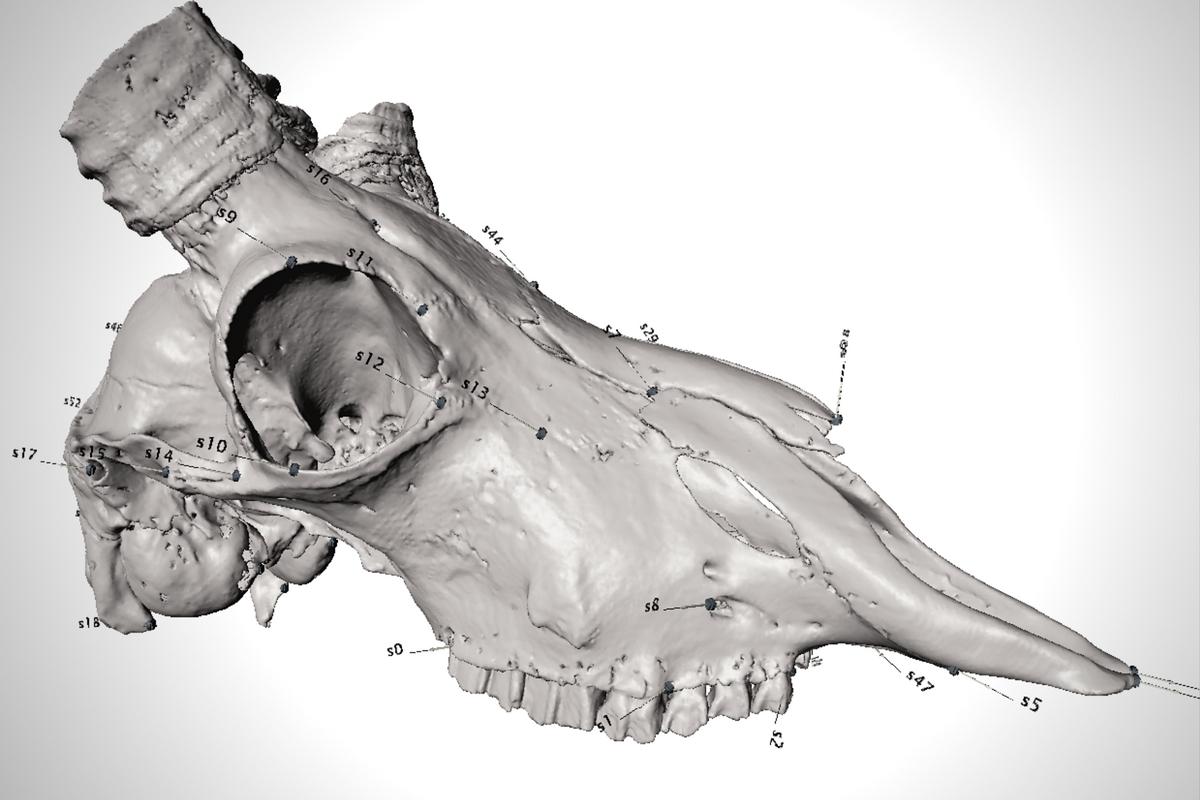

To evaluate how competition might have influenced the evolution of antelopes, our researchers are creating 3D models of a representative set of skulls using a handheld surface scanner. As a next step, reference points – also known as landmarks – are pinpointed on these models in order to compare differences in skull shape. Knowing the evolutionary relationships of fossil and extant antelopes allows us to place the skull shapes into an evolutionary context. Any major shifts in form can be pinpointed along the evolutionary tree. High rates of shape divergence among different coexisting species provide evidence for evolution being driven by strong interspecific competition.

For some time, we have known that climate change has been a major driver of evolution. This certainly applies to Africa, where the environment changed from more forested to more grassy over the last 5 million years. Human evolution itself was strongly influenced by these climatic and environmental changes. The current research project on biotic interactions is on the frontiers of a new approach to our evolutionary past, one that seeks also to determine the role competitive interactions might have played in the context of our own evolutionary history.

Considering that Africa is the continent where humans evolved, we are beginning to ask whether early human ancestors might have negatively impacted the complex webs of competitive interactions among savanna animals. This is especially relevant to the time period during which our ancestors began consuming meat, first by scavenging and eventually by stealing kills and hunting. Early human meat-eaters might have created a new set of rules in the ecological game on the ancient savannas. Our research work can further help shed light on why so many African herbivore species went extinct over the last 1 million years, and whether this might also be linked to the evolution of our species.