The gigantic skeleton of a sauropod dinosaur stands more than 13 metres tall in the central atrium of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. The Giraffatitan brancai is the centrepiece of the exhibition. Sauropod dinosaurs are the largest animals that have ever walked the Earth. Researchers at the museum apply methods from engineering and medicine to look into the way these animals did move about.

3D models

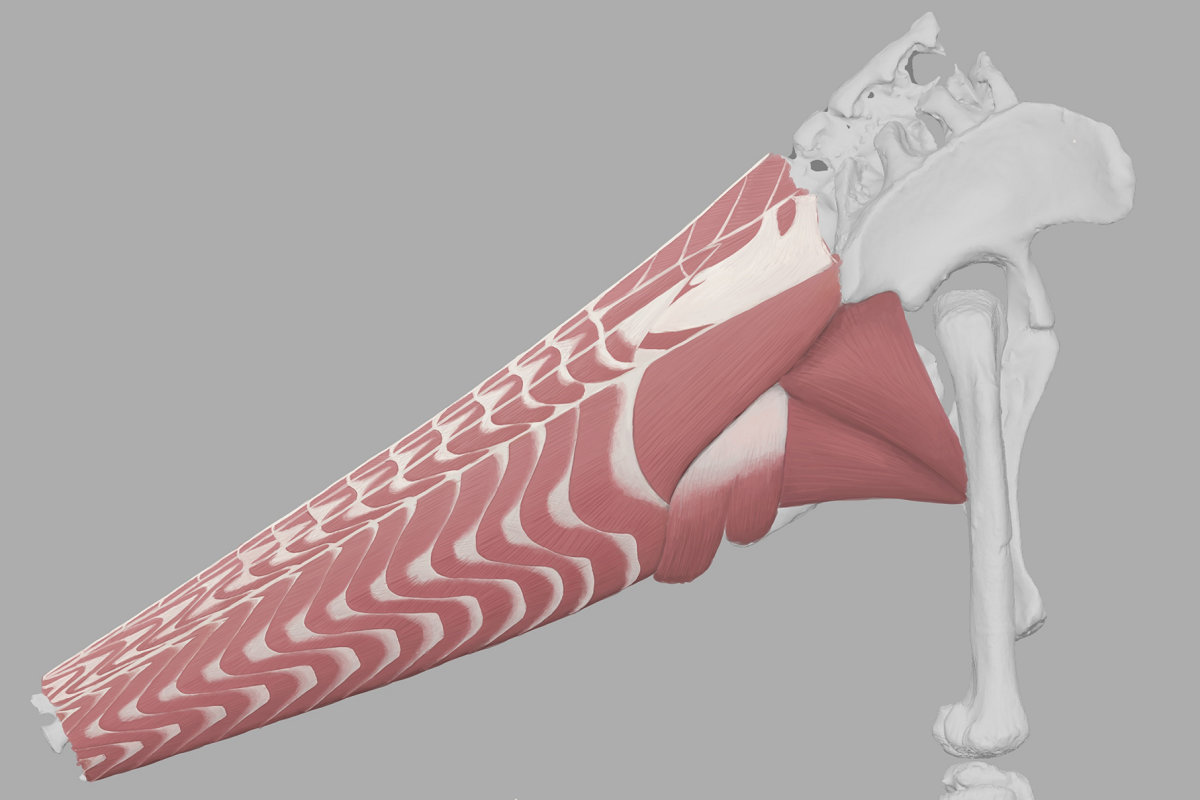

“Our project is one of the first to apply high detail computer models in palaeontology,” says project leader Verónica Díez Díaz. The museum’s collection contains several almost complete caudal vertebral series, i.e. chains of vertebrae that formed the tails of sauropods from the Tendaguru site in Tanzania. The researchers digitised the fossil bones using photogrammetry. The scans show even subtle differences in the musculoskeletal systems of various sauropod species.

Using a special software, a challenging project in itself, Díez Díaz put the bones back together, added muscles and tendons, and drew conclusions about the biomechanics. “We have arrived at more realistic 3D-reconstructions of these animals’ anatomy which help us to understand the biological role of the tails,” says Díez Díaz.

Sauropod body language

In comparison to other sauropods, Giraffatitan has a shorter, more massive tail, especially in the part closer to the body. The researchers assume that it mainly used the tail muscles to support propulsion of the upper part of its hind limbs. The tail muscles were also counteracting each other, so that the tail would not move sideways when the animals walked.

Sauropods with longer tails could have used them in a stabilising way, helping them to support their great weight. Studying the fossil bones also sheds light on behavioural aspects: “We see that their tails have larger ranges of motion which could be related to communication in the herd,” says Díez Díaz. The animals may have used tail movements as body language.

The Tendaguru finds are of immense value to science. However, almost complete skeletons also pose a challenge: the many options of possible movements. There is a large number of bone elements to start from and researchers need to recreate many units of muscles, ligaments and tendons that have not been fossilised. In future research, Díez Díaz would like to study the interaction of the tail and hind limb muscles in sauropods, including a greater part of the body.

Project-title

A “Look Back” in Palaeontology: Reconstructing the Tails of Macronarian and Diplodocoid Sauropods

Funding

Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung