This article was first published in our journal For Nature (issue 5/2021).

From ants to dinosaur skulls: The collection of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin contains a valuable natural heritage. Now it is being comprehensively catalogued and made digitally accessible to the whole world – to help shape a future worth living.

Spheciformes make the first step. Each of the 40,000 animals in the collection of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin will have a digital image. Researchers in Munich, São Paulo or Tokyo will be able to examine the finest details of their powerful jaws, which they use for digging, on screen.

On a November morning, the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin is already working at full speed on the automated mass digitization of the Spheciformes; the individuals of the Crabronidae family are currently being digitized. Digitization technicians take the small Hymenoptera from the collection boxes, stick them with their needles on metal rods and let them travel over a conveyor belt to the cameras. Flashes light up. Each exemplar is photographed from three sides up to 30 times each. Astata boops appears on a screen, sharp from jaw to black and red abdomen – a perfect basis for answering scientific questions, identifying a species, for example.

Over the next ten years, all 15 million insects in the collection of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin will be digitally recorded in this way and sorted into modern collection boxes. The wasps will be followed by bees and ants, then beetles, flies and butterflies. The mass digitization is part of the effort to open up the collection comprehensively and make it accessible to everyone, something that was previously reserved for scientists only.

The opening itself is public: In the new exhibition digitize!, visitors can follow live how several thousand insects are digitized every day. "We want to let people participate in our work and show processes rather than just the results," says Stephan Junker, the Managing Director of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, which is one of eight research museums in the Leibniz Association. "We're all about making visible what it means to digitally access and preserve a natural history collection and to gain scientific knowledge from it."

A place that allows dialogue and participation

With the mass digitization that began at the end of October, the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin is already in the midst of implementing its Future Plan, for which it has been promised 660 million euros by the federal government and the state of Berlin. The money is to be used to renovate the partly dilapidated building on Invalidenstrasse and to create another museum location in the Adlershof Technology Park in order to reposition and research parts of the collection. However, around 80 million euros of the total sum are also available for "collection development" – the digital recording, inventorying, conservation and contemporary accommodation of the approximately 30 million objects, around 80 percent of which are still in historical cabinets and unrenovated collection rooms.

Opening up the collection represents a change of direction in the museum's work – toward more dialogue, participation and relevance. "We have known for 200 years that we are important to the scientific community," says museum director Johannes Vogel. "Our goal now is to enable widespread use by people from different backgrounds and to encourage society to address their questions to us, rather than just answering our own. We want to be a place where people discuss and argue for the best solutions to the problems of our time."

For example, digitizing a small wasp is a way to make it available to global science and enable new ways of looking at the species. But it can also be a starting point for social debates – about climate change, for example. After all, Spheciformes, which love dry, hot habitats, can be a signifier of rising average temperatures or even the spread of deserts.

A collection full of surprises

"The value of our collection lies in the unique objects and the inexhaustible information they contain," says Christiane Quaisser, one of the two heads of the Collection Future science programme, where around 130 employees are working to make one of the world's most important natural history collections fit for the future. "We keep around 170,000 type specimens here, i.e. the prototype specimens for species that researchers from all over the world rely on," says Quaisser. For example, the guppy, which today swims in aquariums around the globe, was first described in Berlin in 1859, as was the extinct Tylacine. The type specimens of many minerals are also stored in Invalidenstraße, such as uraninite, from which the Berlin pharmacist Martin Heinrich Klaproth isolated the chemical element uranium in 1789.

The importance of preserving and opening up such a world collection is shown by the surprising answers that are repeatedly found in it: new species, for example, or missing links in the tree of evolution. In 2016, for example, an international team of researchers found the extinct arachnid Idmonarachne brasieri and recognized in the 305-million-year-old fossil a missing link on the way to today's web spiders. Megalara garuda, a wasp species with monstrous jaws whose males can grow six centimeters tall, had also been hidden in a closet since the 1930s – and was first described scientifically in 2011. Researchers at Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde have produced the oldest indirect evidence of viruses in the Earth's history, they have detected bone diseases in dinosaurs that shed light on the origin of bone tumors, and they have used peregrine falcon eggs to determine why their population in Germany has declined so sharply: because the insecticide DDT causes eggshells to thin and break before the chicks hatch. "So research keeps coming back to our collection objects," Quaisser says.

Saving the skins

But what is to be researched must also be well preserved. "We are constantly fighting decay processes, because many objects decompose naturally," says Quaisser. Conservation methods also were not designed for long-term preservation in the past. "Many of our mammal skins, such as those of zebras or antelopes, are at acute risk of decay because they have been treated with acids or tannins that break down the skin structure over the years." About 80 percent of the 30,000 skins in the collection are at risk, she said. Quaisser and her team have developed methods to save them. "Many of our skins are unique contemporary witnesses," she says. "We now know how to treat particularly valuable specimens to halt decay processes."

Experiments are also underway for other types of objects, such as minerals, to stop aging and decay without, for example, destroying DNA or isotopes with chemicals. If, at some point, someone wants to find out where a particular snail species was in the food chain, what it fed on, or what its habitat was like, it might be necessary to examine a small piece of the original snail for stable isotopes using mass spectrometry. Likewise, objects may contain valuable information that can't even be read yet with current technologies. "We need to secure our collection so that it can continue to provide answers to all conceivable questions in the future," says Quaisser.

Snail shells in a growing cloud of knowledge

Astata boops, the wasp with the black-red abdomen, will develop a virtual life of its own in the future, just like any specimen or fossil in the museum. Via an identification code linked to the physical original via a QR code, Astata boops will be discoverable on the Internet – and will float at the center of a growing cloud of knowledge. "It starts with the basic information on the labels that are scanned, and continues with digital images of the object, such as the high-resolution photographs from mass digitization, 3-D models or CT scans, all the way to DNA sequences and links to relevant research publications," says Jana Hoffmann, who heads the Collection Future science programme with Christiane Quaisser. Experts from the global scientific community and citizen science should be able to enrich the knowledge clouds. "In this way, an ever-larger store of knowledge is being created that incorporates the most diverse perspectives possible, including those from the countries of origin of our objects," says Hoffmann. "It will be networked with other knowledge repositories worldwide via uniform data standards." For this task, Hoffmann is cooperating with technology companies and bringing new professional classes to the museum to work with the collection curators – computer scientists, software developers, media scientists.

In the past, anyone wanting to research the biology of the Beyrich's slit shell had to gather information from scattered specialist libraries, visit natural history collections around the world, including that of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, to study the type specimen there, and decipher old labels. Today, machine learning and artificial intelligence are helping to process the diverse data, for example by recognizing writing or patterns. In the future, all of the Museum of Natural History's objects will be searchable via a Data Portal. "No matter what interests or questions someone has about our collection, she or he need only pull on a thread and get all the relevant information," says Hoffmann. A single object can thus become the starting point for a virtual journey that opens up entirely new perspectives. "You could ask, for example, which objects were collected by women, come from a certain latitude or from a colonial context," says Hoffmann. Or simply sort beautiful jewel beetles by color shades, as the artist Michael Scheurl has done.

Unlike specialized natural history databases, which are often only understood by experts, the Data Portal of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin is aimed at the general public. Thousands of animal voices can already be heard, historical drawings of algae or photographs of grasshopper specimens can be viewed, sorted, downloaded and located on a world map. "We hope that as many people as possible will come up with ideas for what they could do with our digitized material," says museum director Johannes Vogel. "We see ourselves as a partner for the imagination and want to create a resonance that reaches far beyond research." Inspirational workshops with citizen scientists, businesses, educational institutions, artists and the general public have already explored how diverse the uses of the collection could be – and how the data needs to be prepared for them.

Just let others do it

The virtual reality installation Inside Tumucumaque demonstrates how imagination can bring the objects of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin to life. You can hop across the rainforest floor like a poison dart frog or flutter through the treetops like a vampire bat and experience the Amazon rainforest from the perspective of its animal inhabitants – scientifically based on the expertise of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and backed by recordings from its animal voice archive. The virtual reality installation is one of more than 20 collaborations that have already been established with the cultural and creative scene via the Mediasphere for Nature platform.

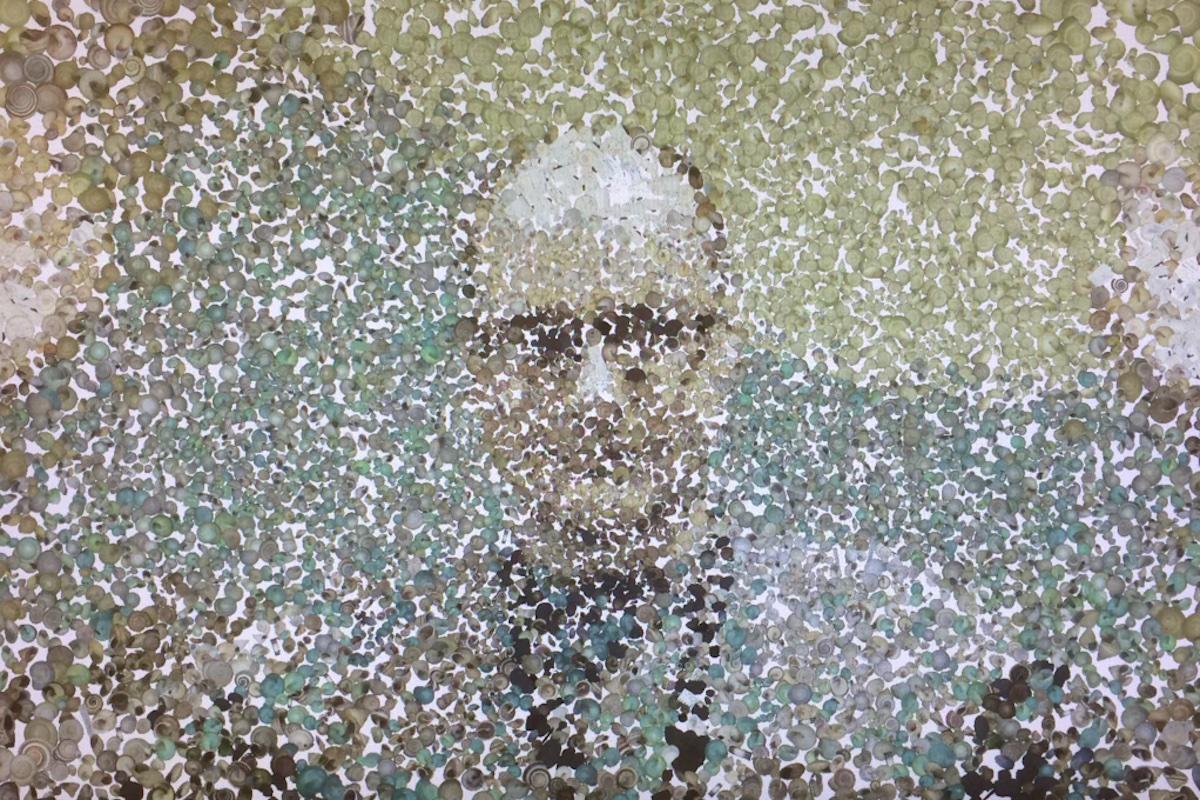

"Digitization can help museums remain attractive to the younger generation and get them excited about their topics at an early age," says Lisa Ihde, who is studying IT systems engineering at the Hasso Plattner Institute at the University of Potsdam. The 25-year-old has already participated four times in the Coding Da Vinci cultural hackathon, in which cultural institutions provide open data for creative software development. Twice she has chosen data sets from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, and programmed the selfie app Snail Snap with her team, which uses 6,000 images of snail shells. The results are artistic portrait mosaics in the muted color spectrum of calcareous shells, backed with biological information about each individual species. The app has won several awards. "Who wants to just look at snail shells lying in drawers," says Ihde. "With Snail Snap, you can engage with them and really have fun."

This year, the Museum für Naturkunde also launched its own hackathon. Under the motto #YourOceanSound, participants composed nearly 30 pieces of music from sound recordings of the underwater world of the oceans, including songs of humpback whales, sounds of penguins or leopard seals, the bursting and "singing" of sea ice, engine noise from ships. "Especially for younger people, this remix idea is very appealing, so to think: How can I change things in the museum, create something new out of them, deal with them artistically?" says Hoffmann. "With collaborations like this, we just want to let go and let others do it."

Knowledge of nature as an insurance policy

But imagination can also lead to concrete innovations. In the inspiration workshops, ideas came up about using spider legs as a template for robots or functional principles of suction organs for the development of underwater equipment – in other words, using animal blueprints for technical developments, an area called bionics. Shark skin has already been used as a model to create low friction swimsuits or marine coatings that protect against barnacles. Shark proteins have also been researched for therapeutic approaches against Alzheimer's disease.

Medicine in general. Many of the active ingredients that protect people from disease come from nature. At the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, for example, a research group is studying the genetic basis for limb reconstruction in salamanders, which regrow lost legs. "The team was able to use fossils to understand that the ability to reconstruct limbs has existed for 290 million years," says museum director Vogel. This led to a project that explores which cells gave rise to bones – and why. "At a time when we are regrowing organs from omnipotent stem cells, we are providing important impetus for applications in medicine with this kind of basic research."

Above all, however, the museum wants to provide impulses for an intelligent and sustainable approach to nature. "Over the last four billion years, life has managed to cope with changes that are beyond our imagination," says Vogel. Just watching the decay of leaves as the seasons change, he says, makes you realize that the perfect circular economy was invented long ago. This wealth, he says, must be harnessed, but prudently. "Natural history museum collections, with their concentrated knowledge, are something like an insurance policy for a sustainable world," Vogel says. "Because somewhere hidden in the DNA structure of nature are endless answers to the big questions we are currently asking ourselves. We want to create access to this knowledge to enable solutions – not for society, but together with it."

Text: Mirco Lomoth

Photos: Pablo Castagnola