Insects are the most species-rich class of animals and make up three quarters of the biodiversity of our Earth. A look through the microscope reveals their richness of colour and shape. Preparator Alfred Keller, who built scientific models for the Museum für Naturkunde between 1930 and 1955, was fascinated by them. During his time at the Museum, he built many unique biological models. His detailed enlarged models of native insects set new standards in the art of museum model building.

Building these impressive sculptures requires many consecutive steps. First, Alfred Keller created plasticine models of which he cast plaster copies. He worked painstakingly on every detail, which had to be replicated in the final paper maché model. Early synthetic materials (celluloid and galalith) were used to make wings and bristles. These were then mounted on the model. Some colouring and partial gold-leaf covering provided the final touches. Such meticulous work took a lot of time and labour. Building just one model could take up to a year.

House Fly

The house fly (Musca domestica) is a member of the Diptera order, in which only the pair of forewings is fully formed, whereas the hindwings have been transformed to club-like halteres. Their vibrating movements stabilise the body during the flight. Adhesive hairs on their feet enable house flies to hold on to smooth surfaces and even sit and move with their heads pointing downwards.

Flies can move their head with two very large compound eyes between which three simple eyes and the short antennae are located. The antennae carry sensory organs for smelling, hearing and the perception of air currents. Flies have taste sensors in the soles of their feet. Their unique proboscis with its two large pad-shaped labella can sponge as well as suck. When feeding, saliva is spread over the food to dissolve it. It is then taken up in liquefied form between the labella and transferred to the mouth.

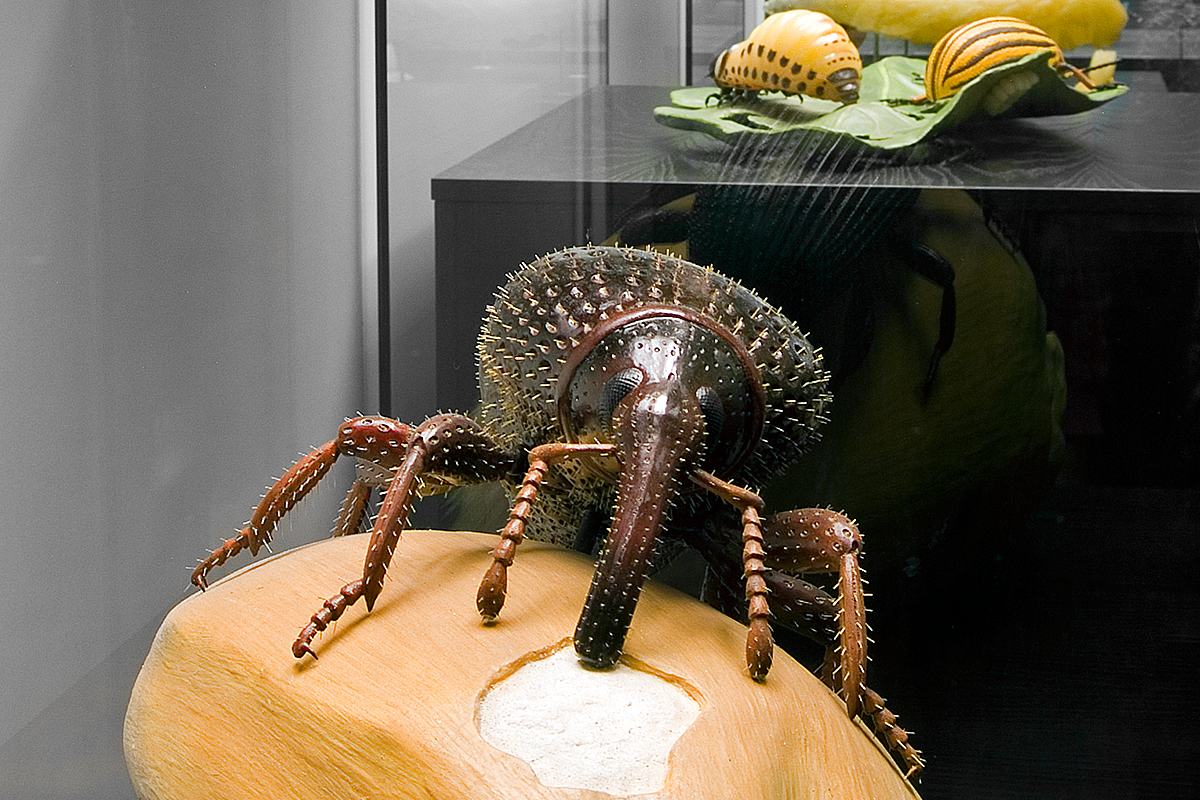

Wheat Weevil on a Wheat Grain

The wheat weevil (Sitophilus granarius) is a member of the Curcolionidae family. They do not possess a mobile proboscis for sucking and cutting, but their head is elongated, reminiscent of a proboscis, with mouthparts adapted to chewing and biting. The females use them to bore holes into grains and deposit their eggs. They use their body secretion to seal the hole. Inside, the larvae feast on the grain for up to two months, then form pupae. After another week, the weevils hatch, mate and produce more eggs. Thus, three to four generations reproduce every year in grain stores. Although they are unable to fly, they spread all over the world with grain transports.

Colorado Potato Beetle with Pupa

Coming from North America, this beetle started conquering Europe only in 1922, from the port of Bordeaux. It spread quickly, and its mass appearance has caused considerable damage to potato crops. Females stick their eggs in little clusters on the underside of potato leaves. A week later, bright red larvae hatch. They first only nibble away on the surface of the leaves and end up eating whole leaves. After two to three weeks, they have changed their skins three times and are ready to burrow into the ground to pupate. After another three to four weeks, the beetles hatch and feed on potato leaves before they are ready to lay more eggs.

Brazilian Treehopper

The Brazilian treehopper (Bocydium globulare) is only about six millimetres long and feeds on the sap of plants. The sap is extracted from the plant tissue with the help of a piercing and sucking beak that acts like a straw. All treehoppers have a high rounded shield over their backs with a rear-facing appendix. Even more striking is the neck shield (pronotum) that sometimes carries bizarrely shaped appendages. Their function remains as yet unclear. It is thought that they may deter predators or serve as camouflage. Treehoppers have the ability of darting off really fast when danger looms. Many species of treehoppers are found in Tropical America, whereas Europe has only three species, one of which has been introduced from America.