Anastasiia Iarkaeva

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, scientists assumed that there was no life beyond 550 meters below sea level. The Challenger expedition (1872–1876) and the Plankton expedition (1889) were the first to shed light onto the diversity of the deep sea. In May 1898 the research ship Valdivia, led by the zoologist Carl Chun (1852–1914), set off to explore the deep sea from the Indian Ocean to Antarctica.

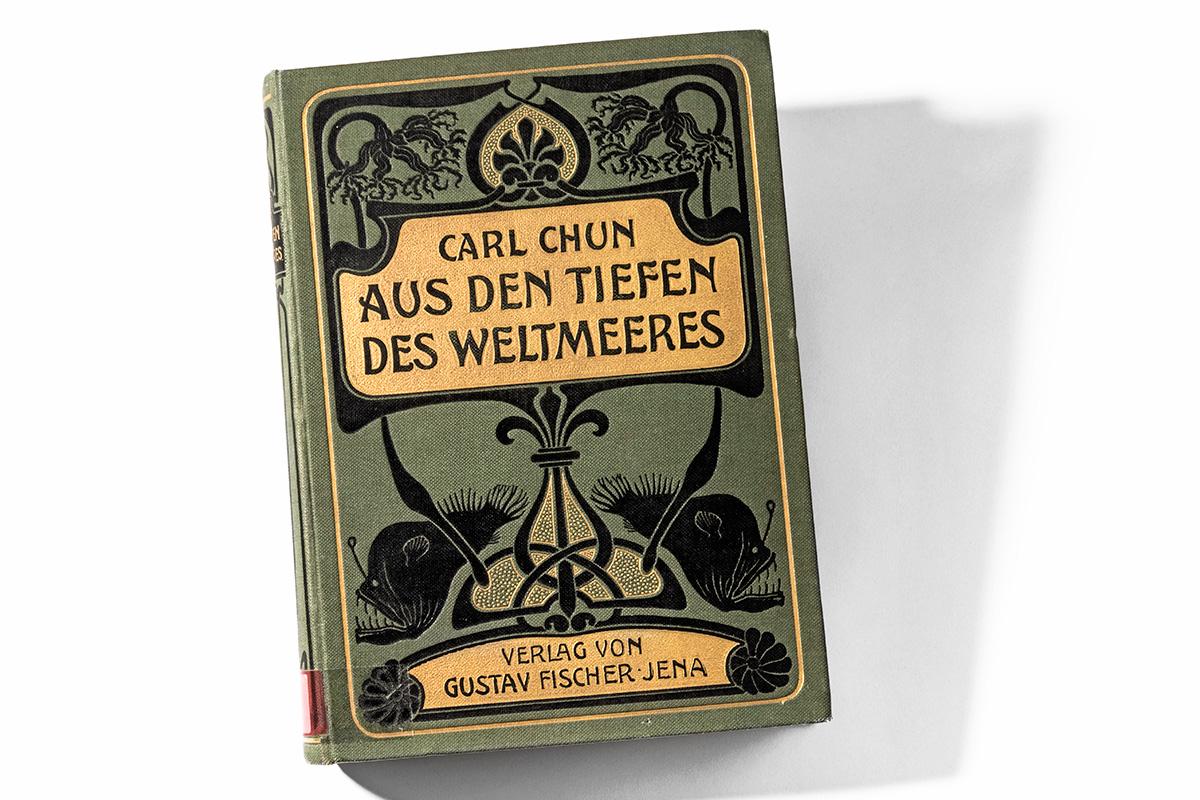

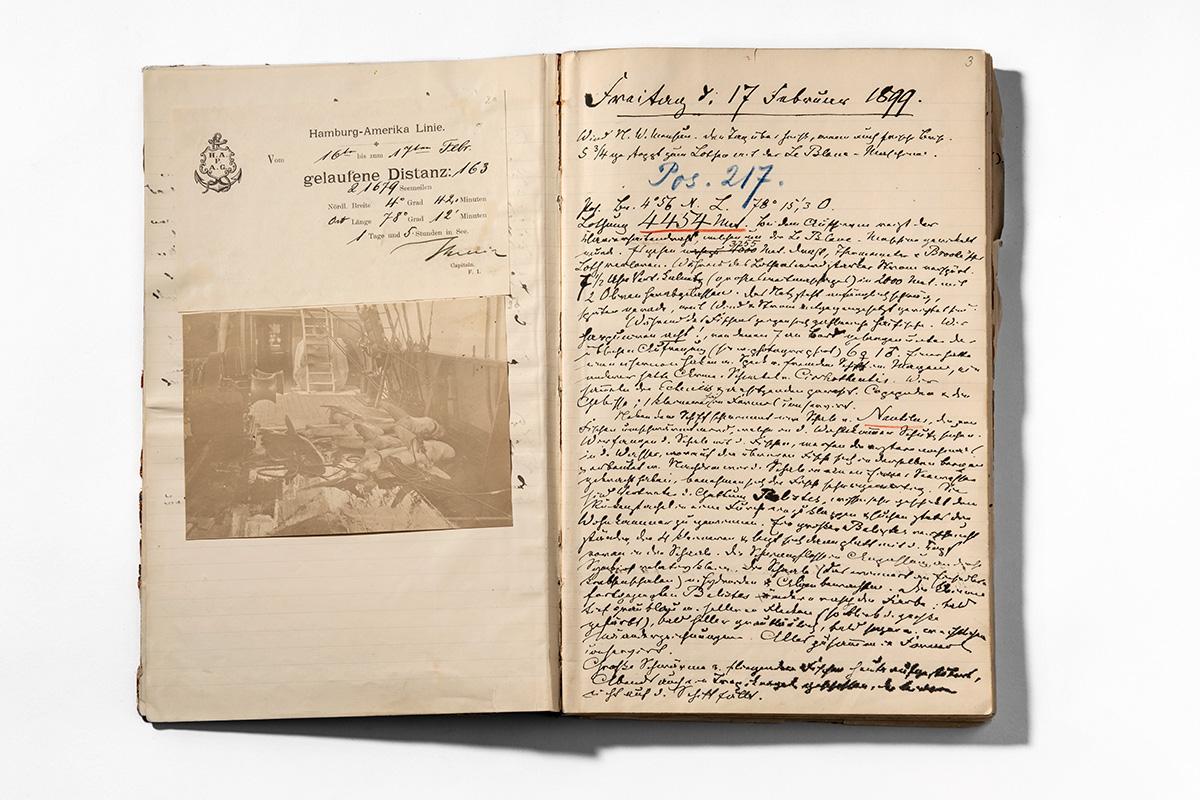

Not only scientific objects were captured by the lens of the Valdivia expedition’s photographer, Fritz Winter (1878–1917). The photographs also documented everyday life on board the ship and may have served, among other things, to legitimize the expenses of the voyage to the Prussian state. In his work Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres (From the Depth of the World’s Oceans), published in 1900, Carl Chun enthusiastically reports on the experiences during the expedition including shark fishing. The glass negative "K001 311" in the Historical Division of the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin offers insights into this practice: The harpooned animal is shown hanging off the side of the ship, while a crew member leans over the railing to get a closer look. An entry from the expedition diary dated February 17, 1899, reveals that, after the harpooning, the stomach contents of the animal were examined. Additionally, the shark’s teeth as well as various crustaceans and suckerfish attached to the animal were of scientific interest for the expedition crew.

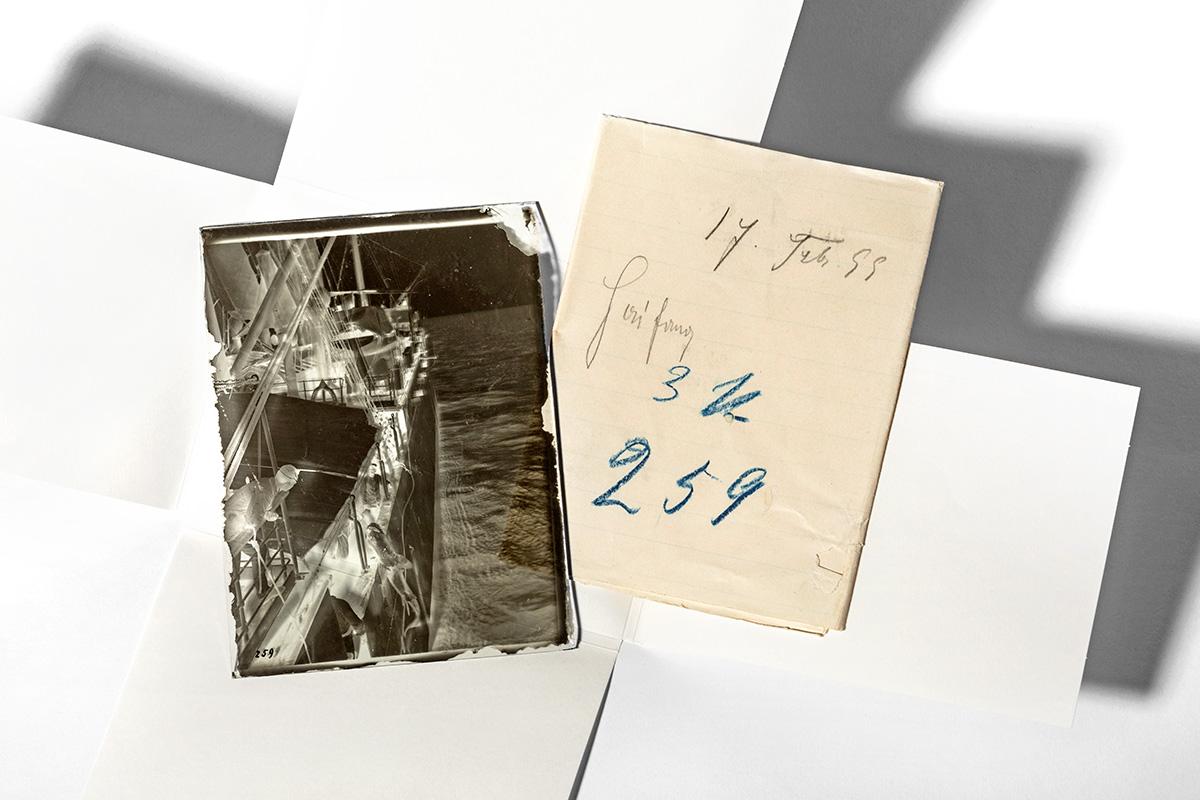

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, the scientific use of photographs – whether in the form of negatives, paper prints, or glass plates – was an already widely established practice. The glass negative of shark fishing is a silver gelatine dry plate in the standard format 12 x 9 cm. It was formerly preserved in a slip of folded paper bearing various notes in pencil and blue wax crayon. One of these notes references the number of the negative, which is also carved onto the photographic plate: "259". The photographer, but also time itself have left traces on the sensitive image surface: On the outer edge of our glass negative, the coating of the over 120-year-old gelatine layer has come loose. Today, this glass plate is stored in archival envelopes and boxes alongside more than 1,500 other negatives and paper slips from the expedition. As a digital object, the negative also "lives on" in the media database of the Historical Division as well as in this online publication.

At first glance, the scientific value of everyday photographs seems of little relevance compared to the research objects collected during the expedition: one is tempted to dismiss them as unintentional 'by-catch'. However, it is precisely these photographs illustrating everyday life on the Valdivia that spark the viewer’s fascination. For the history of science, they also offer insights into research practices at the end of the nineteenth century and help us understand how photographs – as popular media and as scientific instruments – have shaped the relationship between humans and nature.

Object Profile

- Title: glass negative "Haifang" (Shark Fishing)

- Signature: K001 311

- Provenance: document collection of the Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition 1889/99, Zoological Museum, now Historical Division at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin

- Material: silver gelatine dry plate

- Author: Friedrich Wilhelm ("Fritz") Winter (1878–1917)

- Date of production: February 17, 1899

- Place of production: Indian Ocean

- Keywords: glass negative, shark fishing, Erste Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition, Valdivia, Friedrich Wilhelm Winter

Bibliography

- Costanza Caraffa: "'Wenden!': Fotografien in Archiven im Zeitalter ihrer Digitalisierbarkeit: ein material turn", in: Rundbrief Fotografie, vol. 18 (2011), no. 3, pp. 8–15.

- Bodo von Dewitz and Reinhard Matz (ed.): Silber und Salz: zur Frühzeit der Photographie im deutschen Sprachraum 1839–1860, Cologne et al. 1989.

- Hannelore Landsberg: "'Die Wissenschaft wird streng und nüchtern richten...' (Carl Chun 1900). 100 Jahre Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition 'Valdivia'", in: Verhandlungen zur Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie, ed. by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie, vol. 5, Berlin 2000, pp. 75–90.

- Betrand Lavédrine (et al.): Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation, Los Angeles 2009.

- Rudi Palla: Valdivia: Die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition, Berlin 2016.

- Marjen Schmidt: Fotografien – erkennen, bewahren, ausstellen, Berlin/Munich 2018.

- Beatrice Staib: Zwischen Zweckgebundenheit und medialer Eigenständigkeit – Expeditionsfotografie um 1900, unpublished master‘s thesis, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 2014.

Sources

- Carl Chun: Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition auf dem Dampfer "Valdivia" 1898–1899, Jena 1902, DOI 10.5962/bhl.title.2171 (last accessed: 17.10.2020).

- Carl Chun: Aus den Tiefen des Meeres: Schilderungen von der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition, 2. Aufl. 1903, DOI 10.18452/2 (last accessed: 17.10.2020)

- Findbuch: K001 Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition; Laufzeit: 1897–1911 (1999, 2011), Historical Division, Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, 2018.

Image credits

- Fig. 1: glass negative shark fishing, silver gelatine dry plate, Fritz Winter, 1899, 12 x 9 cm, next to paper sheet with notes, MfN, HBSB, K001 Nr. 311, © Carola Radke, MfN.

- Fig. 2: Carl Chun: Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres: Schilderungen von der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition, Jena 1900, library of the Museum für Naturkunde, General Zoology and Entomology, signature Lb 21: F4, © Carola Radke, MfN.

- Fig. 3: Fahrtenbücher (log books), opened to year 1899, with mounted photograph, HBSB, K001 no. 1558, © Carola Radke, MfN.