The striking resemblance between the oldest-known mammalian fossils, which date from the Late Triassic more than 200 million years ago, and little critters like modern shrews and hedgehogs, which are all active at night, led paleontologists to assume that the first mammals had a largely similar lifestyle. Night time activity, or nocturnality, would also provide an elegant explanation for the evolution of a constant body temperature, as this would make the animals independent of cooler conditions in the dark. Finding true evidence for this hypothesis proved difficult, however, because behavioral and physiological traits rarely become fossilized.

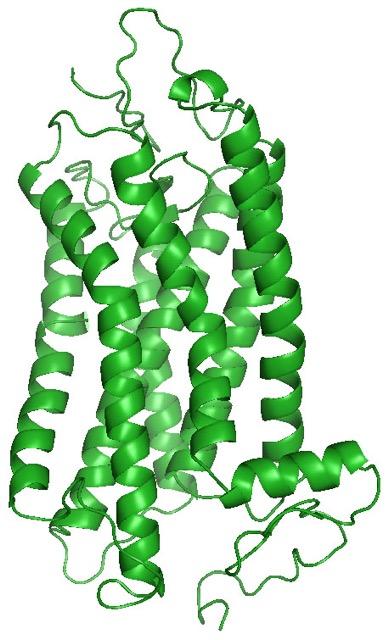

The researchers from Berlin and Toronto therefore chose a different approach. Using bioinformatic methods they traced back the molecular evolution of rhodopsin, a visual pigment of the eye that is responsible for vision at night and under dim-light conditions, up to the origin of mammals in the Triassic. They also computationally estimated the hypothetical gene sequence of the first mammalian rhodopsin and recreated a true visual pigment in the laboratory, which they tested for its function. "The reconstructed mammal rhodopsin shows a light absorption spectrum that is similar to many day-active/crepuscular mammals such as cows, but it also displays several additional features, e.g. the time until it decays, that are otherwise found only in nocturnal animals", says Constanze Bickelmann from the Museum of Natural History Berlin.

The researchers also applied so-called selection analyses to test for nocturnality. "This method is used to calculate the extent of selection pressure acting on a gene or protein, e.g. during times of environmental change or major evolutionary radiations", says Belinda Chang from the University of Toronto. Results showed that remarkable changes must have occurred on the lineage leading to the so-called Theria, which originated roughly 70 million years after the first true mammals and include, among marsupial and placental species, also modern humans. These observed changes are in accordance with recent fossil finds of early therians that witness a dramatic shift in the evolution and ecological diversity of mammals during the mid Mesozoic. "Our results emphasize how important it is that paleontologists and molecular biologists collaborate," says Johannes Müller from the Museum of Natural History Berlin, "as only this way we can get a comprehensive picture of the evolution of life."

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/evo.12794/abstract?campaign=wolacceptedarticle