In Parasitology a research team from Germany and South Africa, including Jason Dunlop for the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, describe a remarkable fossil tick from the Cretaceous Burmese amber of Myanmar. Khimaira fossus combines the body of a soft tick with the mouthparts of a hard tick. It has been placed in a new, extinct family and appears to represent a ‘missing link’ which belonged to a probably even more ancient group from which both the soft and hard ticks may have evolved.

Ticks are not exactly popular animals, but they are a fascinating group of blood-sucking parasites with a fossil record stretching back at least 100 million years. Today, we recognise two main groups. Soft ticks are flattened, leathery creatures such as the pigeon tick and other species which are often found on birds. Hard ticks are more robust creatures and include the ticks usually found on deer, sheep and even household pets and people.

Ticks are represented today by 905 species, all of which feed exclusively on the blood of vertebrates. Several are of medical or agricultural significance as transmitters of disease. 714 are classified as hard ticks in the family Ixodidae, 190 as soft ticks in the family Argasidae, and there is a single unusual species from South Africa placed in a family of its own. The question of when ticks first evolved, and which group of mites they evolved from, remains unresolved. The oldest ticks come from the ca. 100 million year old Burmese amber of Myanmar and include a fascinating mixture of living and extinct groups. In the Parasitology paper the authors describe a remarkable new fossil tick which appears to combine the leathery body of a soft tick with the large, forward-projecting mouthparts of a hard tick. The authors named it Khimaira based on the chimera: a mythical monster combining body parts of different animals. Molecular data suggests that hard and soft ticks probably diverged from each other much earlier, perhaps up to 290 million years ago. The new amber fossil may thus be a late survivor of an extinct group from which the two main families we see today evolved.

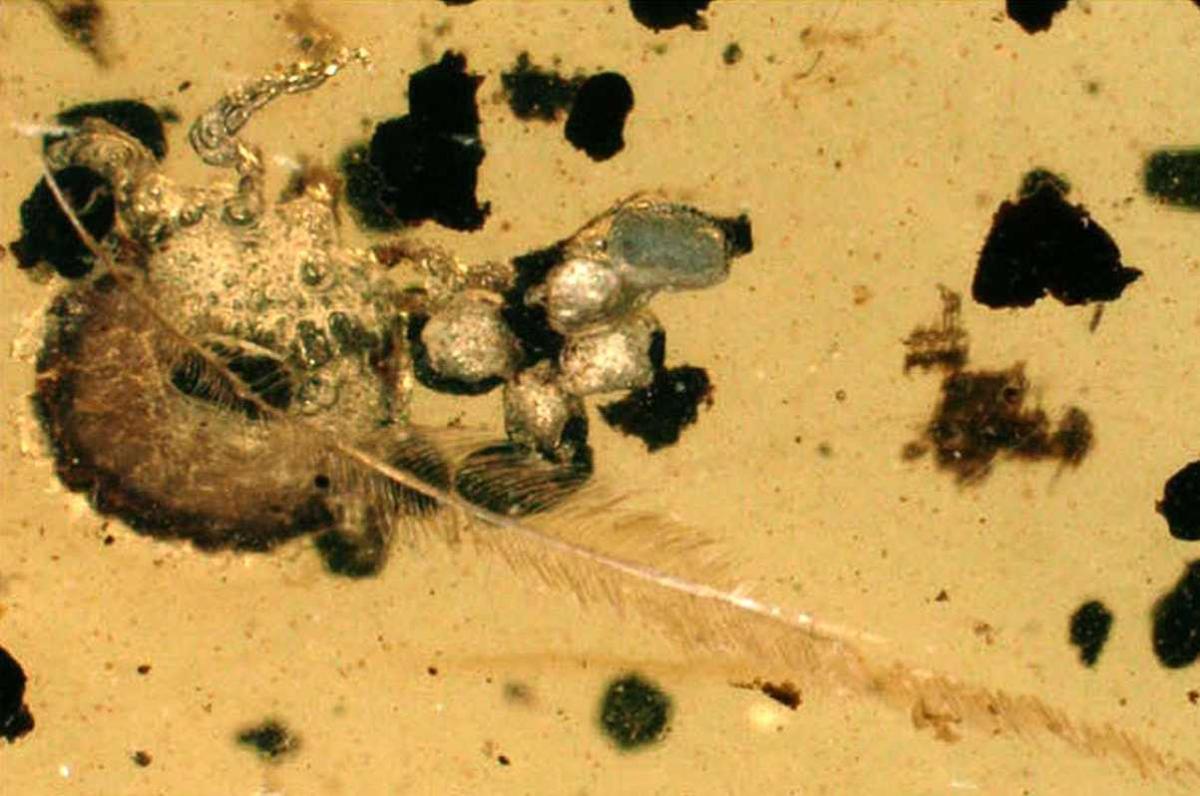

The same publication also describes the oldest example of the hard tick genus Ixodes, a group previously know from the much younger Baltic amber. Living Ixodes species include several ticks of medical importance. This fossil is of particular interest for appearing to be closely related to living Australian species. It adds to an ongoing debate about whether the arthropods found in Burmese amber had their origins in Asia or Australia: one hypothesis being that Burmese amber was deposited on an island which broke off from the northern coast of Australia. Other fossils described in this paper include a different species of tick, Cornupalpatum burmanicum, where an adult female is associated with a feather which may imply that adults of these ticks were feeding on early birds or feathered dinosaurs.

Disclaimer: We acknowledge the current sociopolitical conflict in northern Myanmar that resumed in 2017. We have limited our research to material predating this conflict. We hope that research on specimens collected before the conflict, while acknowledging the situation in Kachin State, will raise awareness of this current conflict and its associated human cost.

Published in: Chitimia-Dobler, L., Mans, B.J., Handschuh, S. & Dunlop. J. A. (2022) A remarkable assemblage of ticks from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Parasitology 149, 820–830. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182022000269

Free press pictures can be found here.