This article was first published in our journal For Nature (Issue 5/2021).

Old expedition diaries, handwritten labels, artistic engravings, biological specimens – the collection of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin is full of rarities and hidden knowledge. Franziska Schuster helps to lift the treasures.

The fish on the yellowed paper has a wing-shaped pectoral fin and three pointed spines under the mouth. Trigla hirundo is written next to it in serif script. The dorsal and ventral fins are reproduced in the finest engraving and carefully colored, so that even after two centuries they still shimmer yellowish-orange. Someone has noted in pencil: "Knurrhahn, 60 centimeters".

This drawing is part of the "Allgemeine Naturgeschichte der Fische" (General Natural History of Fishes) by the physician and naturalist Marcus Elieser Bloch from the end of the 18th century – one of the many treasures in the Zoological Library of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. "In our cabinets are many such original works that are extremely valuable to science," says Franziska Schuster, flipping ahead to a spherical, golden fish with long spines on its dorsal fin, the Peter's fish, Zeus faber. "It's another beauty."

Schuster is a Collection Transformation Manager at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and co-director of the "Transformation" project, which has the task of repositioning the museum's collection for the future, designing a concrete plan for how it can be preserved in a contemporary and secure way and made digitally accessible to everyone. Schuster's specialty is "flatware," as it's called in museum parlance, meaning more or less "two-dimensional" objects: historical collection catalogs, inventory books, expedition reports, diaries, letters, glass negatives, but also animal voice recordings. "We have formulated a desired state for the collection and are now creating the necessary infrastructure," says Schuster, with a mixture of practicality and enthusiasm that it takes to tackle big challenges like this. "For each type of object, we're looking for the most efficient method." For the beauties in Bloch's Natural History of Fish, that means digitizing them with a new high-end scanner without damaging the brittle pages.

You could call Franziska Schuster a treasure seeker, although she doesn't lift the treasures of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin herself, but makes sure that others can dig through the depths of the collection as comfortably as possible. "You never have to look far to bring something great to light," she says. She herself is most excited by the inconspicuous things, a pretty seal on a letter, for example, or a handwritten note in the margin that speaks to her from another time. "I'm sure a researcher is looking for very different treasures."

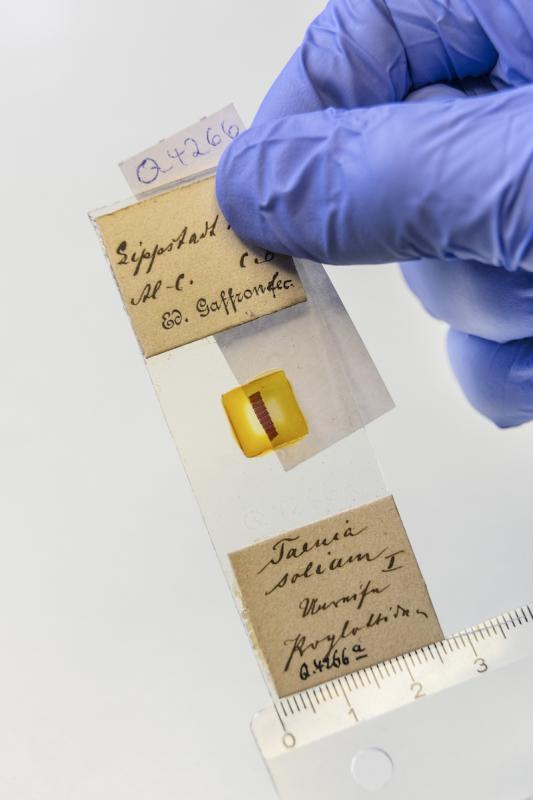

For example, for the tissue sections of macaque embryos, red-stained specimens on glass plates, made for microscopy just over 100 years ago. The embryological collection alone contains 300,000 such microscopic specimens, and there are 600,000 in the museum as a whole, organic and inorganic, mounted on a wide variety of slides: small, large, thick, thin, sawn by hand, made of glass, cardboard, wood, aluminum, plastic – an almost inexhaustible pool for scientific dives. Schuster and her team are developing semi-automated methods to digitize this treasure as well. "The aim is to produce images of all the specimens that are as precise as if you were looking at them through a microscope," she says. This will allow scientists to answer their questions without having to put the historical slides under a microscope themselves.

Schuster came to the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin in 2020. As a media scientist, she had previously worked with "flatware" film, digitizing old GDR animated films for the DEFA Foundation to make them accessible to as many people as possible. She delved into the technical tricks of scanning technology, film restoration and color correction to make the digital copy look as authentic as possible. "And yet, in the end, you always just have a representation of the original on a different medium," she says. "It's questions like these that make the subject of digitization so exciting for me."

At the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, many things came together for her: The opportunity to help shape one of the most extensive digitization projects in German museums, and in an environment that sees this process as core to its future viability. "For me, it was really great to come to an institution where my ideas fall on fertile ground," says Schuster. Here, she is a technician, consultant and playmaker all at once.

Her "flatware" also includes the labels that hang from every single bee and dinosaur bone in the collection. Often, they are just tiny slips of paper with handwritten notes about where they were found, species names or dates. Many objects have received more than one label over time – their number grew with the state of research, species names were reinterpreted, additional information was recorded.

Schuster shows a fossil, fossilized shells of seashells. A beautiful piece no doubt, but what is it? "There are nine labels that have survived for this fossil, all of which contain important information," Schuster says. For example, that they are 175- to 200-million-year-old shells collected by Alexander von Humboldt on his second expedition to America in Peru, that they were described as Pectus alatus in 1839 and later assigned to the genus Weyla.

The label with Humboldt's original handwriting has also been preserved. "Without notes like that, you'd have to reidentify every object, and a lot of things could never be recovered," Schuster says. "That's why our labels are so insanely valuable." Until now, they've been laboriously typed up to make them searchable in databases – a never-ending task. Now Schuster and her team want to train algorithms to automatically index millions of labels. To do this, they are working with companies that use artificial intelligence, for example, to decipher ancient handwriting. "We can use these techniques for other documents, such as inventory books," Schuster says. However, many of the old papers in the libraries and archives of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin first need conservation treatment so they don't disintegrate when scanned. That, too, is part of Schuster's task of saving fragile originals for posterity.

The ten labels on Weyla alata will soon be joined by another label, with an identification number and a QR code. "Anyone who scans this code will be able to call up all the information about the object with one click," says Schuster. Such as being able to trace the finding site on a map or track down other objects associated with the fossil - right down to correspondence among researchers or an expedition report in which it may once have been mentioned. "Digital indexing creates cross-links that add value for researchers and other user groups," says Schuster.

For her, collection development means above all a great responsibility. "In many cases, after all, these are living creatures that once died for research" she says. "So I see it as my duty to preserve them, as best as I can, for future generations and make them available to society instead of locking them away in cabinets."

Text: Mirco Lomoth

Photos: Pablo Castagnola