The large and valuable mineralogical collection of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin is still the subject of intensive research today. Laboratories with mysterious devices such as the cathodoluminescence microscope, the Raman spectrometer or the electron beam microprobe with field emission cathode. However, in addition to these high-tech devices, something completely different contributes to the scientific exploration of the mineralogical collection, its majority dating back to the late 18th and early 19th century.

In addition to the labels, there are documents such as collection catalogues, lists and letters in various old German scripts. "These documents often contain important additional information for research, such as detailed descriptions of the circumstances of the find, and are therefore of great scientific importance," explains Ralf Thomas Schmitt, curator of the Mineral and Petrographic Deposits Collection. However, during routine digitisation and in research projects, there is often not enough time to transcribe these documents, i.e. not only to digitise them, but also to make them readable for everyone. Although computer-aided transcription is possible, the results are still far from satisfactory due to the large number of fonts used. So how can these valuable but difficult-to-access documents be made available? "This is where the citizen science approach with the transcription workshop can help us," answers Ralf Thomas Schmitt.

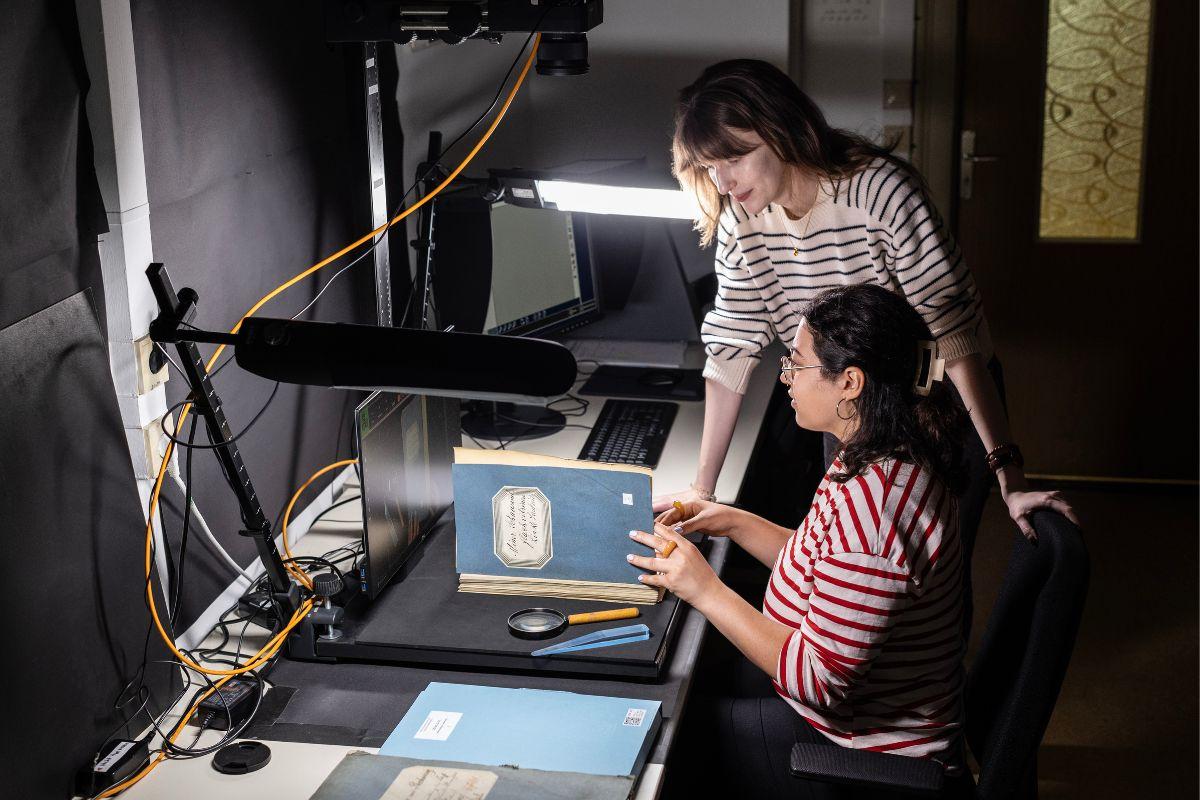

This transcription workshop is a project in the museum's Science Programme "Collection Future", in cooperation with the museum's own archive and the "Collection Discovery and Development" project of the museum's Future Plan. The contact person is Saskia Brunst. "To transcribe our documents, we need people who are fit in palaeography, i.e. who can decipher old writings, and who are interested in transcribing such old documents," she explains. "We now have a strong and motivated team of almost forty volunteers. They help where neither the archivists during cataloguing nor the academics during their research have the time to fully transcribe archival documents."

The entire transcription process consists of four steps. First, the document is scanned and imported into Transkribus, a special software for transcribing. Then it's the volunteers' turn. They begin by "segmenting" the text areas of the document line by line; each line of text on the scan is labelled so that the transcribed lines can later be assigned to the lines on the scan and the two can be compared. Once this has been done, the text is transcribed. In concrete terms, this means that the volunteers decipher the text on the scan and type it in, line by line. To do this, they work in pairs in tandems. At the same time, or as a final, fourth step before the transcript is handed over to the client, so-called tagging takes place. This means that tags are inserted into the text. These are links that connect information in the text, for example places, a date mentioned or persons named, with additional information or with entries in Wikidata. Wikidata is a freely editable knowledge database that was started by Wikimedia Deutschland, the Wikipedia people.

"The transcription workshop is very digital. Everyone works on their own computer and yet, fortunately, we have participants of all ages, from students to over 80-year-olds. What keeps us together are the regular digital meetings, where the latest information is shared and questions are answered. This can be, for example, innovations in Transkribus or a report on the status of the respective research project for which we have transcribed documents. We often also try to decipher difficult text passages together at these meetings."

At present, the transcripts are only sent to those who have requested them for a scientific project. However, the museum's archive is endeavouring to create a platform on which the transcripts can be accessed independently of any academic projects. "Then it won't just be the clients who can use the transcripts," explains Saskia Brunst. "Unfortunately, we're not there yet, but we're working on it."

The Transcription Workshop team can already look back on initial experience in transcribing mineralogical archival material, for example as part of the history of science project "Schwerwiegende Schenkungen" (Heavy Donations) on the donation of several geoscientific collections to the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin in the years 1770 to 1840. For this project by Dr Ina Heumann and Dr Angela Strauß, scientists here at the museum, the "Geognostische Bemerkungen" (Geognostic Remarks) by Johann Anton Stolz (1778-1855) were transcribed. "We are ready. You just have to tell us which mineralogical documents from our archive are needed."