Humans are changing nature with all their power. As a result, science is recognising a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene - the age of humans. Elisabeth Heyne is building a digital collection of all kinds of everyday things at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin that connect people with this new reality.

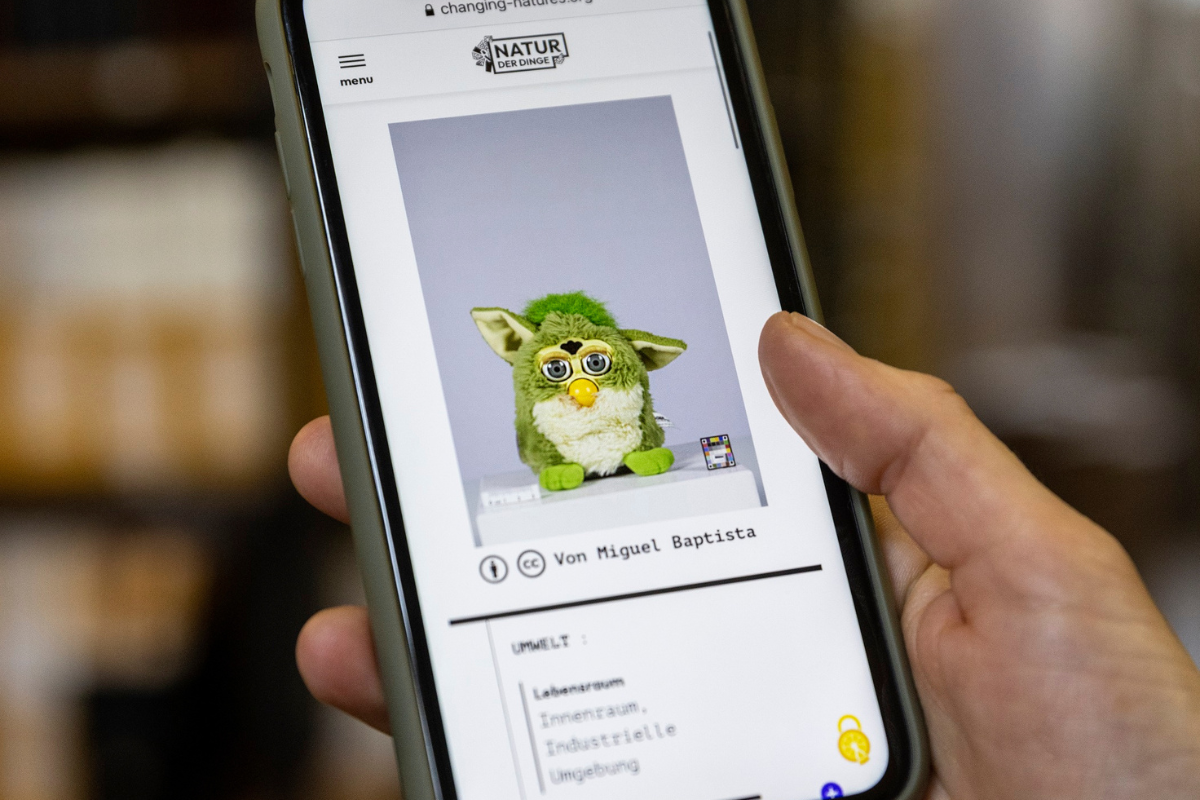

There is Furby, for example. Elisabeth Heyne places the small plush figure with green and white plastic fur on the table in front of her and opens its eyelids. The battery is exhausted. It used to be able to blink, wiggle its ears, and open its beak, even talk. "It's a children's toy that looks like an animal but isn't one, you can't quite tell if it's supposed to be an owl, a cat or a bat," says Elisabeth Heyne.

The 34-year-old is building a completely new collection for the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin and in collaboration with the Paris Museum of Natural History. These are not finds from scientific expeditions but from very personal daily objects that anyone and everyone can contribute. Objects that stand for the new age into which humanity has led the earth: the Anthropocene. They show how humans have become a determining factor in the Earth system and intervene deeply in natural processes.

Furby, this half-creature of owl, bat and cat, had only been on the market for two years when the term Anthropocene entered the public consciousness around 2000. "It is characteristic of our time that we build artificial, hybrid animals that our children can then play with," says Heyne. One senses how she loves to look into things with a kind of X-ray vision, to look for a second level, a cultural one on which stories take place and connections are revealed.

As a literature scholar, it is natural for her to dissect the great concepts of our time and to put them under the microscope and examine them. Something that natural scientists would do with an organism. Heyne is particularly interested in the life of terms like "Anthropocene": how each individual person perceives the Anthropocene and all the changes it represents. This is what the things in the collection are supposed to tell us about. "Nature of Things" - in French "Histoires des Natures" - is a digital collection whose objects are uploaded to a central platform as photos, sounds or short videos and which is designed to constantly grow.

It already contains around 150 objects that can be browsed online, displayed on a map, commented on and expanded with one's own observations. Furby is represented there just as much as a snowman, a ball of electrical waste or a postcard "from Aunt Hedwig" from 1962 that shows the green Harz Mountains - with healthy spruces stretching to the horizon. The owner:s of the card have also uploaded a second Harz view, from a hike in autumn 2022 - with dead trees stretching to the horizon. "We hope that nature is strong enough," they wrote. "Many people ask themselves: what is actually happening around us here right now?" says Heyne. "With the collection, we want to understand how they perceive the change in the environment on their own doorstep and their own role in it."

Elisabeth Heyne was already tracing concepts and terms for her doctoral thesis at the Technical University of Dresden and the University of Basel. She asked why Western modernity tends to categorise the world. Why the world distinguishes fact from fiction, nature from culture - and thus has turned nature into something foreign that can be exploited without hesitation. Two years ago, she was informed of a call for applications from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin to lead the Anthropocene collection and saw a great opportunity. "I really wanted to do science in close exchange with society," she says. Shortly afterwards, she entered through the venerable portal on Invalidenstraße. A humanities scholar alone in the wide corridor in a museum where class, order and kind count. Strict biological facts. But not at all.

"There is a whole department that looks at nature with a cultural and social science view," Heyne tells us. "This interweaving of cultural knowledge and the collection objects is unique for a natural history museum." With the digital collection of the Anthropocene, Elisabeth Heyne is now going one step further. This is because it is being created in dialogue with society. Anyone can upload a photo of an object and write something about it on the website naturderdinge.de. The platform automatically translates all texts into French and English.

Heyne's team also organises collecting workshops with students or invites people at events to dig in the depths of their pockets and handbags for Anthropocene objects. In this way, a trilingual database is growing up that contains very personal stories about environmental change and the relationship between humans and nature. "We want to learn from people instead of just passing on our knowledge," says Heyne. After all, for a long time it was the natural history museums that shaped an image of nature that contributed to many of the problems of the Anthropocene - and which therefore urgently need to open up to new ways of seeing.

If Elisabeth Heyne wanted to upload an object herself, which she deliberately does not do, it would be a piece of brown coal. Like the one she brought with her from the mineralogical collection. A brittle, dark brown lump that, after millions of years, still hints at the structure of the tree to which it once belonged. For Heyne's "X-ray vision" it is: "ancient, condensed organic matter that we burn in seconds to generate electricity and through which we fuel the climate".

She grew up in Lausitz, witnessed lignite mining as a child and watched the region become one of the driest in Germany. With the help of the collection, she hopes to initiate discussions about such processes and raise awareness that all our actions have an impact on nature. This includes the realisation that the Anthropocene was largely caused by industrialised countries, but that the negative consequences are mainly felt in the Global South.

"Anthropocene is a distorting term because it looks at the world mainly from a Western perspective, but it is immensely helpful to get into the conversation that humans urgently need to do relationship work with nature," she says. "I think that many people already realise that not everything can always be bigger, better and faster."