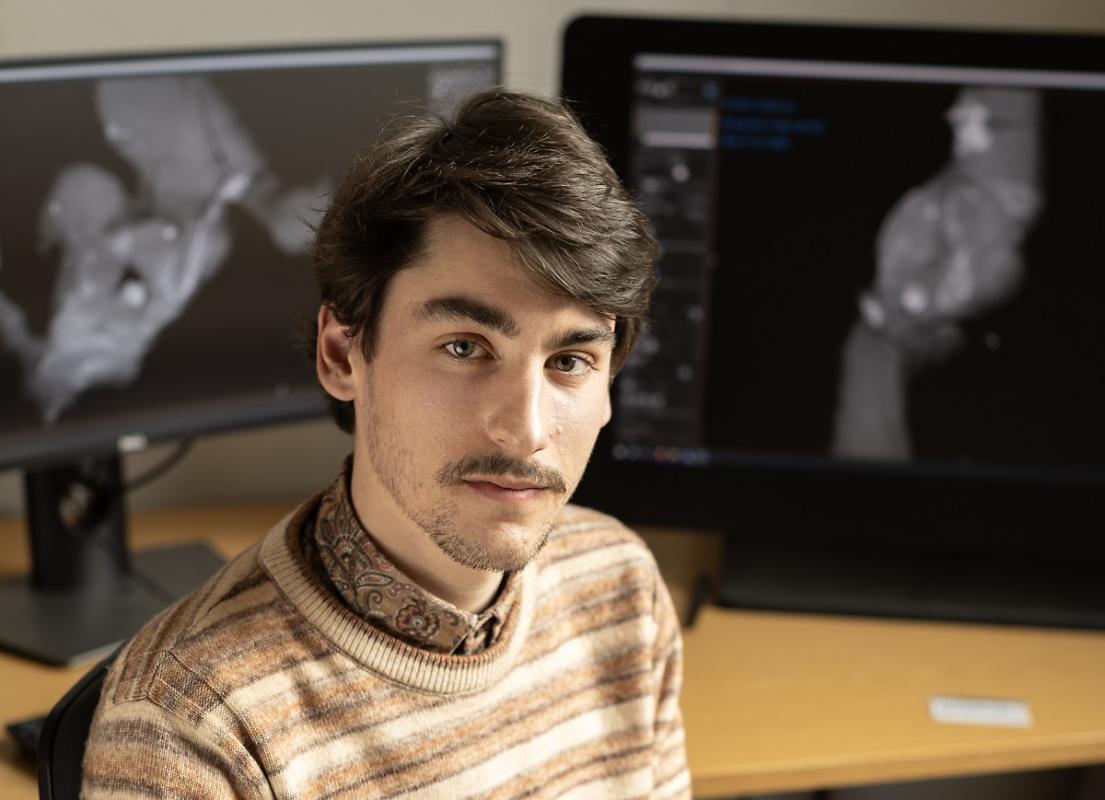

What does this tiny bone cluster tell us? Arnaud Rebillard investigates (un)digested remains of vertebrates, discovered at Bromacker.

This article was first published in our journal for Nature (issue 11/2025).

With great enthusiasm, Arnaud Rebillard holds a reddish-brown rock fragment about four centimeters in size in his hand. “This is the first one ever found at Bromacker!” he reports, his eyes sparkling with excitement. Only on closer inspection do two tiny bones, scarcely two millimeters long, become visible. This is no ordinary stone. It is a coprolite, fossilized feces. In other words: around 290 million years ago, a small carnivorous tetrapod (Ursaurier), approximately one meter in length, searched for prey in what is now the Bromacker area. It found what it was looking for, ate smaller vertebrates and then excreted the indigestible bones. These are now being analyzed by Rebillard.

His excitement grows as he takes a second fragment from the collection cabinet. This one contains a tangled cluster of bones. It is a so-called regurgitalite, meaning indigestible material that a predator had regurgitated and which has now been preserved as a fossil. It is the first find of its kind from Bromacker and was recovered during the 2021 summer excavation.

The special nature of this rock was not immediately obvious. Initially, the researchers noticed small protrusions in the rock, took the piece along as a precaution, and brought it in for preparation. During this process, the sensation became apparent: it was a regurgitalite consisting of numerous, but mostly disarticulated bones and, unlike a coprolite, not embedded in a “sausage-shaped” matrix.

Rebillard is a specialist in the field of bromalites. These are fossils representing (un)digested remains that have subsequently become petrified. Since 2023, he has been working on his doctoral thesis, focusing specifically on coprolites and regurgitalites from Bromacker. During his master’s thesis, he already examined similar material from other sites. However, the finds from Bromacker are particularly remarkable, as they consist of fossilized remains of terrestrial vertebrates. Coprolites and regurgitalites are more commonly found in areas that were formerly oceans, seas or lakes. “I am fascinated by the rarity of this material – regurgitalites in particular are extremely uncommon. They allow us to study so many interactions between animals of that time. All of them lived in the same place at the same time. Larger predators at the top of the food chain fed on smaller animals, possibly including juveniles or insects. Through this research, we can reconstruct and understand an entire ecosystem.”

To study the bromalites thoroughly without damaging them, state-of-the-art technology is employed. Three-dimensional scans of the specimens are created using a CT scanner at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, and the resulting images are subsequently segmented. This method makes it possible to identify and separate the different materials in the scans. In this case, the bones are distinguished from the surrounding matrix inside the bromalites. The bones appear brighter in the scans because they are denser than the surrounding material.

After the data are segmented along all three axes, the software generates a 3D model of the segmented bones inside the bromalites. The tiny bones can be digitally enlarged and examined from all angles within the 3D model. This enables researchers to determine what the prehistoric predator fed on. Extensive comparative material from the collection is available to assist in this analysis.

The collection at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin contains multiple cabinets holding several hundred coprolites and regurgitalites from around the world. These are to be examined gradually, and the data will be made publicly accessible. Thousands of potential predator-prey interactions could still be discovered here, and hundreds of additional ecosystems could be described and compared in greater detail in the future. Large collections like this constitute an important infrastructure for addressing future research questions. Making them accessible for everybody is a central goal of the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin’s future plan.

Recently, it has become apparent that curious things can come to light in this process. George Frandsen, founder of the “Poozeum” in the USA, and Andreas Abele-Rassuly, collection manager for palaeozoology at the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, searched through the collection of more than 1.2 million vertebrate fossils for the one that had been the earliest to enter the collection. They found two coprolites with small, faded notes in old German handwriting from the 19th century. A team deciphered the content and encountered a sensation: the natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt and the Scottish geologist Sir Roderick Murchison shared a fascination for coprolites! Humboldt had received these two coprolites from Murchison.

Rebillard’s publication on the unique coprolites and regurgitalites from Bromacker will be released soon. There are still many boxes full of unexamined finds from the excavations at Bromacker in recent years. What else might be discovered that will then require further study?

Text: Gesine Steiner

Photos: Pablo Castagnola