This article was first published in our journal For Nature (issue 2/2020).

From tiny to huge: the museum digitizes its objects using the latest methods. Scientists from all over the world will be able to research them on their home PC in the future.

How fine are the hairs of millimeter-sized ants, bees or beetles? Often thinner than any human hair, that's for sure. This is why such fine hairs and other tiny objects from the museum's insect collection are difficult to digitize in three dimensions, i.e. in 3D. But what about the tail vertebrae of giant dinosaurs like the Giraffatitan brancai? The size and structure of dinosaur bones are difficult to compare with wafer-thin bees' wings. A single method is therefore not enough to transfer the museum's collection with its 30 million objects into the digital world.

"We are currently concentrating on three techniques: computed tomography, known from medicine, structural light scanning and photogrammetric methods," says Frederik Berger, scientific director of the collection digitization. Computed tomography provides detailed insights into the interior of an object; however, the data does not contain any information about the coloring of the objects. In a structural light scanner, an iron-sized device casts light on the bones. The captured reflection creates a 3D image - this is particularly useful for research on large fossils or ungulate skulls. In photogrammetry, special software is used to first create a point cloud from several photos from different angles. The software then uses this to generate 3D geometry. Zoom in, turn around, view from above or below: none of this is a problem with 3D objects.

"With the complex 3D technologies, we only record particularly valuable objects or objects that are essential for research work," says Berger. These include the type specimens: These are the individuals on the basis of which the species was first described. Which process the digitization team uses depends on what information the researcher needs and what object it is.

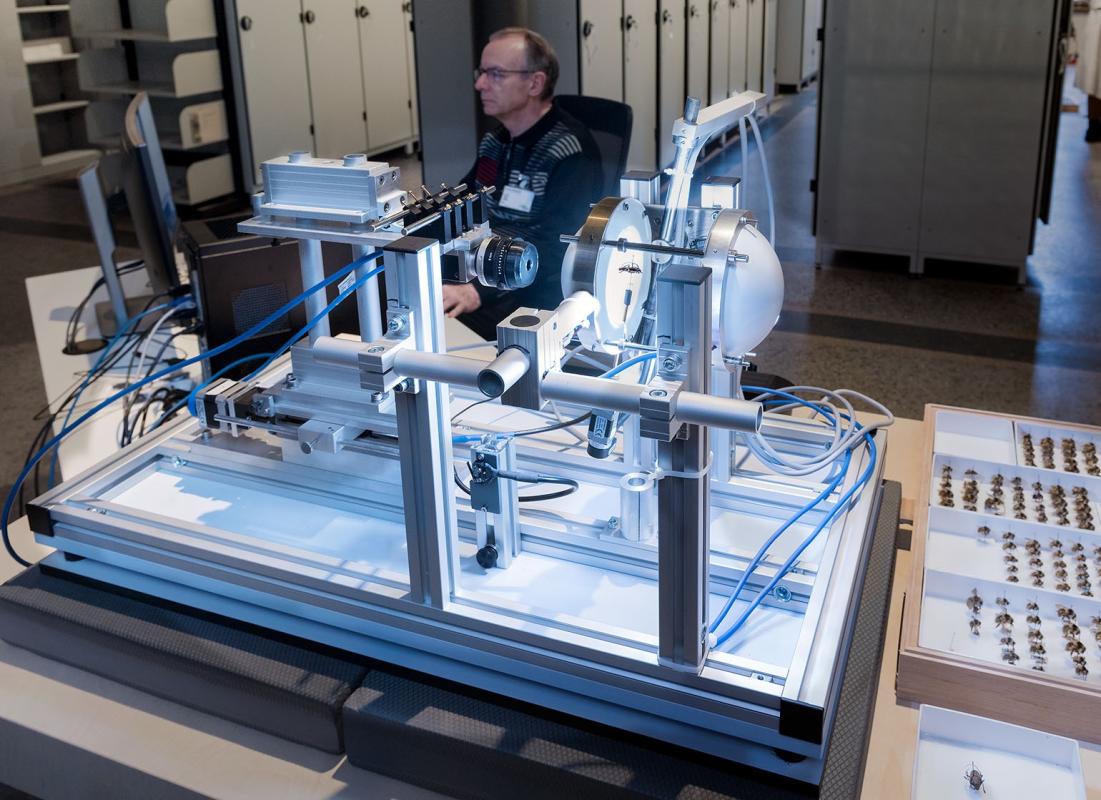

The museum recently owned the Darmstadt insect scanner Disc3D, developed by the non-profit association DiNArDa e.V. It is the world's first 3D scanner for insects from museum collections. Around 25,000 images, each with 12 megapixels, are combined to create images of sharp depth from almost 400 perspectives around the insect. This makes it possible to depict even the smallest insects and their wings and hairs in three dimensions. Researchers from all over the world can work on insects that are hundreds of years old in 3D at the click of a mouse.

In the museum's micro-computed tomography laboratory biological, palaeontological and geological objects are analyzed using computer technology. The laboratory is a central point of contact for both research at the museum and for digitizing the scientific collection. "The computer tomographs built especially for research can be used in a wide variety of ways. This means that the smallest internal structures, such as the auditory organs of insects that are a few millimeters in size, and ungulate skulls up to 40 centimeters in size, can be measured down to the micrometer", says Kristin Mahlow, a technician in the computed tomography laboratory . What does it look like inside a primeval bone? Or in a rare line from the wet collection? The latest technical methods allow a view into the objects without any destruction.

The digitization team at the museum will digitize all 30 million collection objects in the coming years. The 3D digitization is only one component of the digitization at the museum. "We often type in analogue text sources such as the collection labels for the objects by hand," says Berger. "That is also digitization."

The aim of all these efforts is that people – researchers as well as laypeople – can access the objects in the research collection via a portal. Insects or ungulate skulls made of megabytes may soon conquer the home screen.

Text: Carmen Schucker