1.MB.DTE.Dia 01, Historical photograph of Tendaguru with storage hut, ca. 1910 ©Archive MfN

The extensive, globally relevant research collection of the MfN can be described as an archive of knowledge for answering questions about the past, present, and future. At the same time, however, the history of the institution and the collection is inextricably linked with the history of colonialism. The project "Research and Responsibility: Virtual access to integrated fossil and archival material from the German Tendaguru Expedition (1909-1913)" is part of the Museum’s efforts to ensure the transparency and accessibility of collections from colonial contexts, and to develop international cooperation with partners in the regions of origin of the objects from which the objects originate.

The collection of fossil vertebrates and related written and photographic material that the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (MfN) holds from the German Tendaguru Expedition (GTE) (1909-1913) can be regarded in equal measure as part of the world cultural and natural heritage. The core of the collection is formed by 225 tons of dinosaur material, accounting for approximately 5000 single bones plus 5 skeletal mounts of the dinosaur species Giraffatitan brancai, Dicraeosaurus hansemanni, Kentrosaurus aethiopicus, Elaphrosaurus bambergi and Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki. The material was excavated in an area that spans around 80 square km around the Tendaguru, a landmark hill near the coastal town of Lindi in southern Tanzania. The fossil bearing strata of the so-called Tendaguru Formation are dated to the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian-Tithonian), and are therefore between 157 and 145 MA old. In addition to the fossils themselves, the material of the GTE at the MfN comprises extensive documentation of the excavations, which were carried out under colonial conditions, and related documentation of later periods in Germany. The photographs, correspondences, administrative files, account books, diaries, drawings and the like are stored in the Archive of the MfN and provide an indispensable source for multidisciplinary research.

What makes the Tendaguru fossils specifically fascinating and complex objects is not only their outstanding palaeontological but also their historical significance. They were excavated between 1909 and 1913 in the then colony of German East Africa, a region in modern-day Tanzania. In this respect, the fossils from Tendaguru are paradigmatic colonial objects, evidencing the more often than not violent colonial collecting practices. For a couple of decades now the fossils from Tendaguru have not only been part of restitution claims by Tanzanian researchers, politicians and the public, but are also at the centre of critical debates and investigations of the colonial history of natural history collections, of science and of museums.

The project "Research and Responsibility: Virtual access to integrated fossil and archival material from the German Tendaguru Expedition (1909-1913)"

The contested past of the Tendaguru collection as well as its popularity and importance for the sciences and the humanities, is contrasted by the fact that the processing of all materials of the entire Tendaruru expedition has so far only been carried out in rudimentary form and is primarily guided by individual scientific interests. The current patchy state of digitisation of the paleontological and historical Tendaguru materials does not do justice to the outstanding importance of the collections for natural and social science research, which is increasingly based on comprehensive digital resources.

In this project, we aim to create a contextualised digital collection by combining all digital contents (object digital models, data, images and documents, archival materials, results, publications) of the GTE in one data platform. The data platform will be globally and interdisciplinary accessible for scientists and corresponds to the FAIR and CARE Data Principles. Making the data available worldwide will serve as a resource for different communities of all countries to develop their own research approaches or use the data for publicity for variable purposes, and will support everyone in their research/approach, thereby promoting equal chances in science and humanities research.

Our vision

Based on the knowledge of the violent history of colonial objects, we are developing a model for responsible cataloguing, presentation and research that treats archival and palaeontological data as inseparable.

Our mission

We are making the heterogeneous colonial Tendaguru collection from south-eastern Tanzania accessible virtually. We link the palaeontological and archival data to highlight their shared historical context. We develop standards for sensitive curation of these colonial collections and bring them together in a research environment. In this way, we are creating a virtual collection that can be further researched, enriched and transformed.

Material

In its piloting part, the project lays focus on material of the iconic sauropod Giraffatitan brancai and the small ornithopod Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki that includes slightly more than 1100 bones, while other fossil material will follow later.

Giraffatitan brancai in the exhibition of the MfN ©Carola Radke, MfN Berlin

Giraffatitan brancai is the most popular dinosaur from the Tendaguru expedition and its skeleton forms the centrepiece of the main dinosaur exhibition at the MfN. Giraffatitan belongs to the sauropod dinosaurs, the largest land-living vertebrates ever. It was a ca. 23 m long and more than 13 m high plant-eating dinosaur with a remarkably long neck and a small head, columnar limbs and a weight up to 38 metric tons. Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki is the smallest dinosaur from the Tendaguru region. It was a small, plant-eating and bipedal bird-hipped dinosaur and its fossils were found in huge quantities at the Tendaguru. This dinosaur is also historically significant, as colonial history is immortalised in the name of this species. The species was named after Major General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, commander of the German colonial army in German East Africa during the First World War. The cruel and inhumane warfare under his command claimed many African lifes. After the First World War, Lettow-Vorbeck demanded the return of the German colonies.

Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki in the exhibition of the MfN ©Hwaja Götz, MfN Berlin

The archive material from the GTE comprises a large number of different historical sources, comprising field photographs, correspondences, administrative files, account books, diaries, drawings and the like. These historical materials form a unique source for dealing with palaeontological and historical questions and allow contextualisation of the fossils.

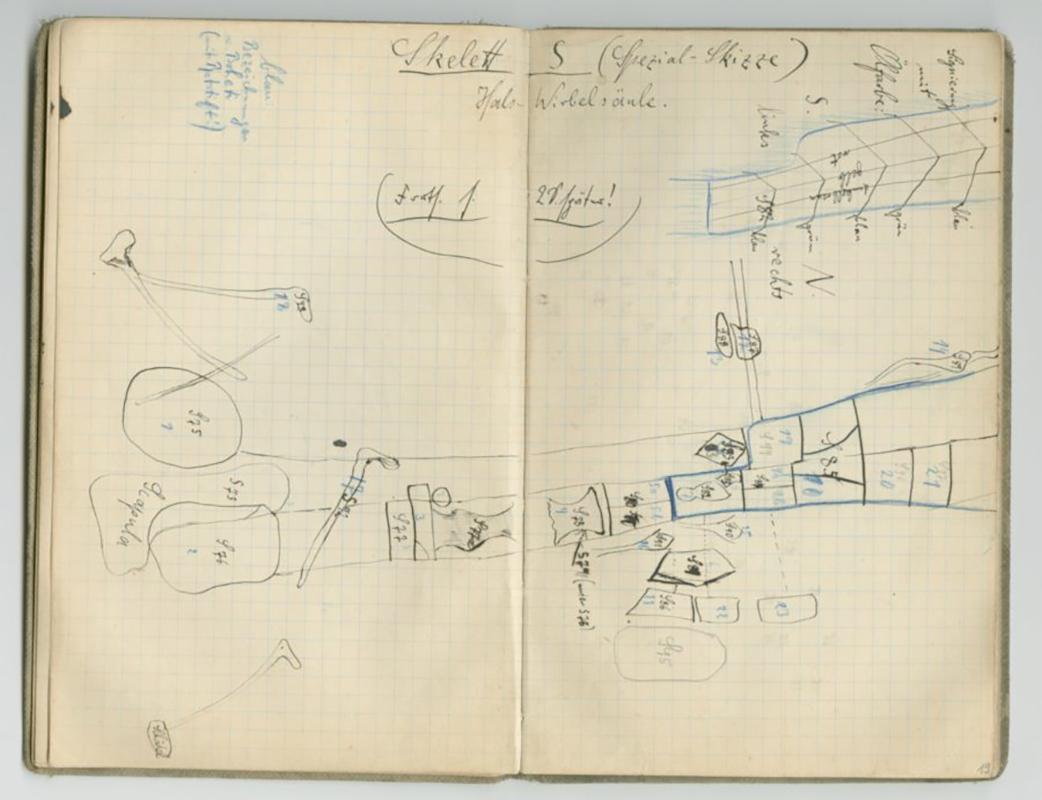

PM_S_II_Tendaguru-Expedition_8_2, Field sketch Giraffatitan quarry ©Archiv MfN

Methods

Following Digitisation and Preservation Best Practices, one of the first tasks was the identification of preservation intervention points (PIPs, sensu Golubiewski-Davis et al., 2022) specific to this project and its objectives, such as the purpose of the created data, selection of digitisation devices and techniques, appropriate repositories, identification of data, metadata and paradata, files to be saved, how and where, etc. These PIPs are constantly evaluated and adapted through the project development.

a) 3D digitisation

Through the process of this project, workflows and techniques for suitable methods of 3D digitisation of larger collections of fossil vertebrates will be assessed, and procedures for integrating and making digitally available research objects from colonial contexts will be established. This includes also the capturing and storage of various metadata.

The different workflows for the capture of 3D topologies from various fossil objects (varying in terms of size, surface complexity and colour) aim to create high-quality 3D models of each specimen. A suite of different techniques for 3D digitisation, mainly based on manual and semi-automated structure from motion photogrammetry and structured light surface scanning is used, in particular:

CultArm 3D: a semi-autonomous scanning station fitted with a PhaseOne iXG 100MP camera; capable of capturing challenging surface materials (e.g. reflective or very dark surfaces) and complex surface topologies that other methods struggle with.

CultArm 3D im Einsatz am MfN ©Eran Wolff, MfN Berlin

Artec Scanner (Spider/Leo): two structured light surface scanners used to digitise objects with simple topology and non-reflective surfaces: Artec Spider is being used for objects between 5 cm and 30 cm and Artec Leo is for objects larger than 30 cm.

Artec Leo beim Scannen eines Dinosaurierknochens ©Eran Wolff, MfN Berlin

Specimens smaller than 7 cm are digitised with macrophotography and focus stacking, testing the suitability of these methods in terms of the quality of the created meshes. Objects of specific interest will also be scanned with Computed Tomography.

All digital objects derived from one of these techniques are later assessed with regard to the overall quality criteria for high-quality 3D models. The workflow includes also the steps from generating 3D models to their storage in the respective long-term storage at the Zuse Institute Berlin and in the public research repository Morphosource.

b) Databases, contextualisation

The collection data from the fossils is stored in Specify, the collection database of the MfN. In order to link the information from the fossil objects in the collections with the historical data in the archives, additional fields are added to specify. Vice versa, for linking the historical documents with the fossil objects, and for a general contextualisation of the project, digital indexing of archival data related to the two chosen taxa Giraffatitan and Dysalotosaurus is achieved and reflected. The information about the historical sources is stored in the archive database ActaPro.This provides a direct connection between all objects.

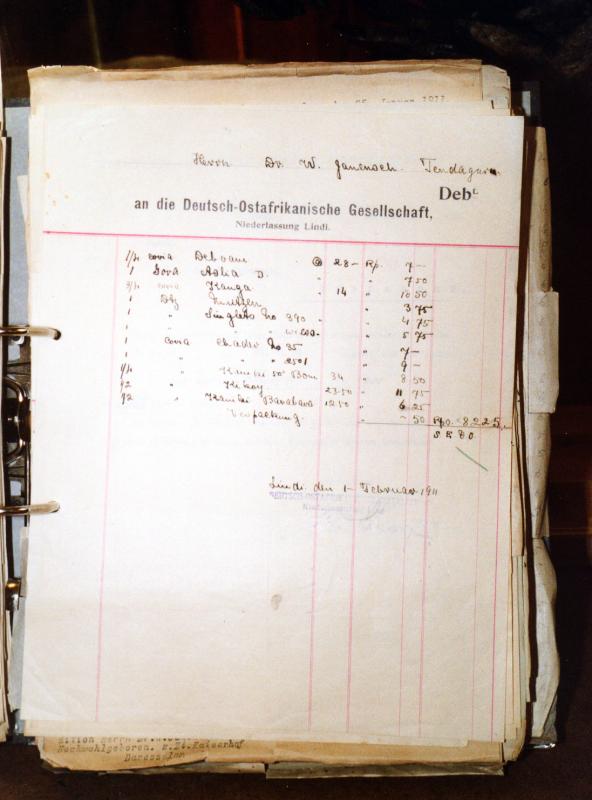

PM_S_II_Tendaguru-Expedition Transportliste aus Tendaguru Akten ©Archiv MfN

c) Research platform

We are currently building a WissKI based data platform as a research portal to display and make the data available. We also follow up on current debates on colonial museum objects by answering fundamental questions about best ways of making them accessible and the role of digitisation in the search for how to deal with colonial objects. This touches on subjects about the languages used, the integration of local perspectives and epistemologies, the hierarchisation of knowledge, and the improvement of visibility of local actors.

Publications

Díez Díaz, V., Akhlaq, S., Kaiser, K., Heumann, I., Schwarz, D. 2025. Digitization as a research methodology in colonial natural history collections. Nature Reviews Biodiversity 1, 145–146. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00031-2

Depraetere, M., Akhlaq, S., Díaz, V.D., Heumann, I., Schwarz, D. 2025. Virtual Access to Fossil & Archival Material from the German Tendaguru Expedition (1909–1913): More Than 100 years of Data-Meta-paradata Management for Improved Standardisation. In: Ioannides, M., Baker, D., Agapiou, A., Siegkas, P. (eds) 3D Research Challenges in Cultural Heritage V. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15190. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-78590-0_8

Díez Díaz, V., Akhlaq, S., Campbell, A., Depraetere, M., Mahlow-Tillack, K., Heumann, I., Schwarz, D. 2025. Risks and Responsibilities: The German Tendaguru Collection as Cultural Heritage and Its 3D Digitisation. In: Ioannides, M., Issini, G., Oliveira, D. (eds) 3D Research Challenges in Cultural Heritage IV. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13577. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-93753-8_5